Nutrition is an important social determinant of health. Food insecurity and malnutrition are associated with poor health outcomes – including higher rates of certain diseases like diabetes – and higher health care costs. Food insecurity and inadequate diet quality disproportionately impact groups with low socioeconomic status. Developing effective Food is Medicine interventions for these populations is critical in improving health outcomes, reducing health care costs, and reducing health care disparities.

Individuals with low socioeconomic status (SES) face a number of barriers to obtaining healthy food and maintaining a healthy diet. Patients may purchase foods that are cheaper per calorie but high in sodium and added sugars, which are associated with diet-related disease. They may not be able to access healthy food retailers, whether due to the absence of such retailers locally or patients’ lack of transportation to such retailers.

A growing body of research suggests that addressing food insecurity and diet quality in low-income populations may be an important strategy in reducing health care costs and improving health outcomes and quality of life for these individuals. One potential strategy to address this problem is the community-supported agriculture (CSA) model as research suggests that participating in a CSA may improve diet quality and health outcomes for members. However, the traditional CSA model presents a variety of barriers for low-income, food insecure individuals to participate.

In a typical CSA model, members pay a farmer in advance for a growing season and receive a periodic (usually weekly) “share” of the produce grown during that season. This model commonly allows consumers to buy higher quality produce at a lower price. Annual cost of CSA farm shares range from $400-$700 depending on length of the harvest season and the variety and quality of products provided.

The high price coupled with the “pre-pay” model of CSAs often inhibits low SES individuals from participating in such programs. Unfortunately, this population may benefit the most from interventions and programs that improve diet quality and health outcomes. Ensuring that CSA programs are accessible to low-income consumers both through state-sponsored food assistance programs like the Healthy Incentives Program (HIP) and through health care system as a Food is Medicine intervention is a critical component of a robust strategy to mitigate food insecurity, improve health outcomes, and decrease health care costs in Massachusetts.

Recognizing the opportunity for subsidized CSA programs to lower financial barriers and improve access for low SES individuals, a new study investigated the impact of a subsidized CSA share on diet quality for individuals at high risk of diet-related illness. Leading Food is Medicine researcher, Dr. Seth Berkowitz, in partnership with Just Roots, a community farm and CSA in Greenfield, MA, led the study of subsidized CSAs as a nutrition intervention in Franklin County, Massachusetts. Franklin County has lower median household income levels than the Massachusetts average and higher rates of food insecurity. For this study, Dr. Berkowitz and his colleagues recruited adult patients with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 in Franklin County. BMI was used to select patients as a BMI greater than 25 25 kg/m2 is associated with a higher risk of diet-related disease. Median income of the precipitants was 146% below the federal poverty guideline. In total, the study recruited 128 eligible participants, 122 of whom completed all of the study visits.

In the study, the researchers provided a $300 subsidy to purchase a CSA at Just Roots to 56 patients (the intervention group). The total price for a share was either $690 for a “full share” (9 items/units of produce per week) or $480 for a “small share” (6 items/units of produce per week). Each week, patients would select their number of items from 15 to 20 types of produce available that week. The farm also provided 2 recipes for patients to aid in preparing the produce in the CSA.

As a control, they gave a similar group of 66 patients (the control group) $300 in cash over the course of the study along with a healthy eating guide. The only restriction on the way patients in the control group spent this money was that they could not use it to buy a CSA membership at Just Roots.

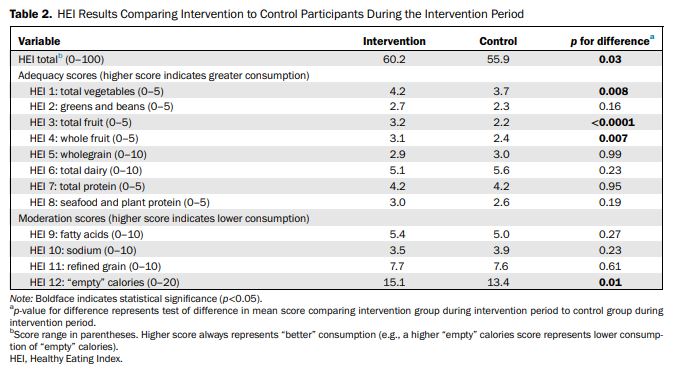

Dr. Berkowitz and colleagues tracked the patients through the 2017 and 2018 growing seasons. They used a tool called the Healthy Eating Index, a measure of overall diet quality, to assess the impact of the CSA subsidy on patients’ diet quality compared to the cash value of the subsidy alone.

Key findings:

-

Participants receiving a CSA membership that provided a weekly farm produce pickup from June to November saw increased Healthy Eating Index scores (4.3 higher, 9% CI=0.5, 8.1, p=0.03) compared to individuals who recieved healthy eating information and financial incentives similar to the intervention group.

-

Analyses of HEI subscores revealed significant improvements in categories clearly associated with the food provided (total vegetables, total fruit, and whole fruit) and lower consumption of empty calories, such as sugar-sweetened beverages.

-

The difference in decreases in food insecurity between groups, adjusting for baseline food security, was in favor of the intervention (RR=0.68, 95% CI=0.48, 0.96).

Further research should be done to explore if these promising results can be replicated in other populations and geographic areas. The promising results of this study suggest that a subsidized or cost-offset CSA may be an effective method for improving diet quality while reducing food insecurity in low-income populations. Given the high impact of diet-related disease on these groups, subsidized CSA shares may be an effective way to improve health care outcomes and reduce costs.

Despite this promise, CSAs remain largely inaccessible to low-income individuals – the typical CSA participant is affluent, white, and highly educated. The 2014 federal farm bill allowed CSAs to accept SNAP benefits as payment for the first time, but this has not led to widespread use of SNAP benefits for CSAs.

Massachusetts, for example, began a SNAP-CSA Pilot Program in 2014 through a waiver from the federal government allowing the state to modify certain requirements for SNAP payments, making it easier for farms and the state to process SNAP payments for CSAs. In addition, the state began a program called the Healthy Incentives Program (HIP) in 2017 that provided a dollar-for-dollar match of SNAP benefits spent at farmers markets, farm stands, and CSAs, making CSAs more financially feasible for SNAP beneficiaries.

Despite these programs, the number of CSA farms in Massachusetts that accept SNAP for their CSA is low – out of more than 200 CSA sites in the state, only 10 have SNAP-CSA members. Given the wealth of opportunities for SNAP-CSAs in Massachusetts, it is puzzling that less than 5% of CSA farms offer such a program.

Given the promise of CSAs as a nutritional intervention in low-income populations, the Health Law Lab is working to identify and analyze the opportunities that currently exist and the barriers to expanding these programs across Massachusetts in order to provide recommendations for CSA providers, government officials, and advocates.