Food insecurity refers to the inability to consistently obtain adequate food due to financial barriers. Recently, there has been an emerging research on the prevalence of food insecurity and its implications for health outcomes.

A 2019 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association analyzes the prevalence of food insecurity across the Medicare population, in which beneficiaries are 65 years or older or younger than 65 with long-term disabilities. Using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) 6-item food security questionnaire, respondents were asked about their ability to afford food and eat enough food.

Out of the total population of 50,685,869 Medicare enrollees, a sample of 9,674 survey respondents was analyzed. It was found that nearly 4 in 10 enrollees (38.3%) younger than 65 experience food insecurity, and nearly 1 in 10 enrollees (9.1%) 65 years or older experience food insecurity. Across both age groups, low income status, having 4 or more chronic conditions, depression, and anxiety were all associated with food insecurity, suggesting that poor eating negatively affects health outcomes and access to basic needs. CMS has emphasized food insecurity and other social determinants of health in its Accountable Health Communities model, in which the social needs of beneficiaries are screened and addressed to thereby improve health care costs and outcomes.

“It was found that nearly 4 in 10 enrollees (38.3%) younger than 65 experience food insecurity, and nearly 1 in 10 enrollees (9.1%) 65 years or older experience food insecurity.”

This relationship between food insecurity and poor health can largely be attributed to malnutrition, financial trade-offs between food and medical care, and functional impairments, particularly in the elderly population. Among children, research has shown that food insecurity is associated with cognitive problems, aggression and anxiety, asthma, suicidal ideation, and worse oral health. Food insecure adults have increased rates of mental health problems, diabetes, hypertension, and poor sleep.

These examples demonstrate the ways in which limited nutrient intake can directly contribute to negative health outcomes. Even more, financial trade-offs can perpetuate these health concerns. For example, a food insecure diabetic will struggle to afford a diabetic diet and medications more than his food secure counterpart. In addition to the nutritional detriment of food insecurity, the lack of financial stability associated with it will further reflect on the individual’s health by inhibiting adherence to medical recommendations. Food insecure individuals will often delay or forgo medical care, under-use medication, and consume low-cost, low-quality food, to mitigate their limited financial resources. Summarized succinctly in the EAT-Lancet Commission, food insecurity and malnutrition pose “a greater risk to morbidity and mortality than unsafe sex, alcohol, drug, and tobacco use combined.”

Source: Gunderson et al., Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes, Health Affairs, 2015.

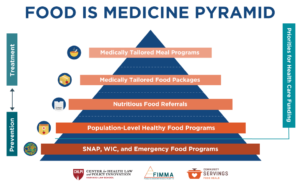

Approximately one out of every ten households in Massachusetts experiences food insecurity. Provided the connection between food insecurity and poor health outcomes, this prevalence amounts to $1.9 billion in health care costs each year. In response, Massachusetts published its Food is Medicine State Plan, consisting of several healthy food-based interventions aimed at those with or at risk of developing serious health conditions related to diet. The designed interventions in the plan, including medically tailored meals, medically tailored food, and fresh produce vouchers, are predicated on the connection between nutrition and chronic disease.

Source: FoodisMedicineMA.org

In addition to CMS’s Accountable Health Communities model, an extensive body of research suggests that Food is Medicine interventions could be effective in alleviating the negative outcomes among food insecure Medicare beneficiaries. One study found that receipt of medically tailored meals was associated with 49% fewer inpatient admission and a 16% reduction in total health care costs. Another study showed that diabetes self-management and distress improved for type 2 diabetes patients after 6 months of medically tailored meal intervention. A third study concluded that a 30% subsidy on fruits and vegetables for Medicare and Medicaid enrollees would prevent 1.93 million cardiovascular disease events and potentially save $39.7 billion in lifetime health care costs if implemented nationally.

Overall, Food is Medicine interventions improve health outcomes for chronic conditions and reduce total health care costs. There is strong evidence to indicate that its interventions would be successful for any population, certainly including Medicare beneficiaries.